…everything looks like a nail.

And well… that’s typically considered “bad”, because it really constrains the way you look at things.

As a beginning coder, I’ve often heard this hammer analogy used in the context of “there will be many more things to learn” and I’ve personally intepreted it as “don’t get comfortable, you don’t know nothing yet.” And I never liked that.

To make a different kind of analogy, from when I used to write SEO content. I remember looking at job listings and seeing different ads that were looking for SEO Writers that specialized in “toothpaste” or “soap” – as if someone writing content about soap couldn’t figure out how to write about toothpaste and vice versa. From that time, and even before (because of my interest in the arts), I always felt the thing that separated the Master Artist from the merely aspiratonal ones was that the aspirational ones often defined themselves too much by the tools they used as opposed to their general ability to solve any problem in any medium.

In Irving Stone’s novelization of Michelangelo’s life The Agony and The Ecstacy, Michelangelo’s most burning passion is to sculpt – and yet, because of circumstances – and his desire and his will to be simply the best… we know him mostly for his fresco on the roof of the Sistine Chapel; a single instance of his ability – and not the class of genius he was.

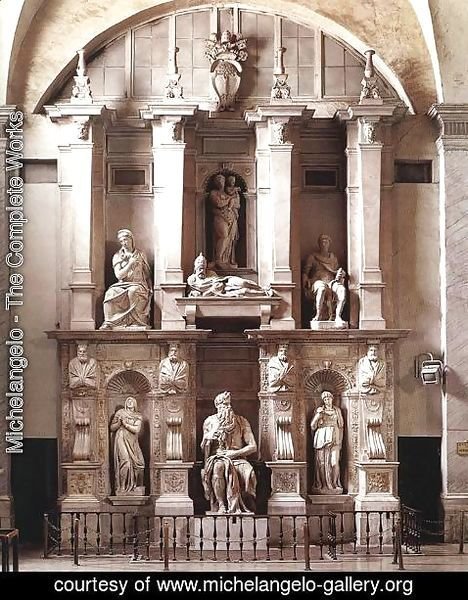

Consider the tomb of Pope Julius which Michelangelo may have personally ranked higher than his work on the chapel.

And here’s another work of Michelangelo, fulfilling the role of architect.

SO, the point is, the one I’m trying to make in regards to hammers is: that while Michelangelo could make use of many “tools”… he himself was a one of a kind hammer that could turn any problem he faced into a nail. Sorta like Thor’s Hammer: Mjolnir…

In essence: it doesn’t matter what the problem is. You come it at with the same force of process, every time. And so… that’s how I came about the title for this technical blog to chart my learning progress; this isn’t just a blog to reflect on the specific skill of programming, but perhaps moreso a blog for me to refine an approach to problem solving. Thus, while I may not have all the tools necessary to be a success (as of yet), making a mission of breaking problems into their smallest component parts will serve well in any circumstance.

………………………………………………………….

In the About section of this blog, I make reference to Eliyahu Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints. I’m not an expert on TOC, but it’s essentially a one-size-fits-all approach that gives you the ability to tackle any problem… from manufacturing, to marketing, to retail, and relationships. And, one would assume even software.

Though the specific solutions one might come up with will be as different and varied as the problems they’re meant to solve – the process is always the same. It is the “Thor’s Hammer” of all problem solving processes. At least that’s how I found it when I came upon it.

NOTE: I found out about Eliyahu Goldratt’s book The Goal while reading The Everything Store which is about Jeff Bezos. In the book on Amazon, the Goldratt book comes up as one of a handful that had a profound influence on Bezos and Amazon. So, I felt like I HAD to read it, and am grateful that I did.

While there is much about TOC (Theory of Constraints) on the internet, most of which (in my opinion) has been warped into cringeworthy management jargon, I’m going to attempt a swing at it for anyone who has read this far and is curious. And also to see how well I can articulate what I think I understand (but am not quite sure if I fully do).

What you do is:

- You figure out what are the constraints of the situation. In other words, what’s the “box” you’re in?

- Given that you can’t change the box, you accept it and work to figure out the causual relationships between the respective problems so you can identify how to minimize their effects – and even use them to your advantage.

- You iterate through all the problems you have until you can get a sense of the one or two big problems that are the cause of all others. It’s all about getting perspective and seeking understanding.

- You then work to solve the biggest problems which will cause a chain reaction that will help you power through all the other lesser obstacles. NOTE: this step almost seems like magic. Especially because, until you have that moment when you attack what seems like the root cause… it seems like you have lots of disjointed problems, a cloud or swarm of problems, that may be unrelated and thus impossible to overcome in any logical order.

- You iterate through these steps, until you have essentially smoothed out all the obstacles by rearranging and reconfiguring your obstacles in such a way that they are no longer weaknesses but perhaps even strengths. The final yield is something that seems so obvious that you almost feel stupid – it seems like common sense… but in fact, the realization at this step was in hindsight difficult to acquire NOTE: this may be because there’s a lot of momentum from life and society about doing something in a way that “people” generally consider to be “right” but which is in fact “wrong” or inefficient.

To apply the above to the coursework… The problem I was initially facing was working really hard to understand certain beginner concepts that would then be replaced soon thereafter with more effective methods. By attending as many study groups as I could, and asking as many questions as possible, and with the help of awesome instructors… I had the realization that if I continued to slog through trying to memorize beginner ways of doing things, that I would likely doom myself to being a beginner for longer than I had to. I made a point to ask myself – how does an expert know what to do, and why.

With that in mind, I realized the goal/objective was not to ace any specific lab with brilliant/clever beginner code, but to move through the course as quickly as possible – to build a foundation to expand on – and to have as large a context as possible, in order to facilitate quicker mental mapping/memorization and to have an idea of what can be done.

Since there are specific tests in rspec that labs must pass, I realized I could accelerate progress by skipping over the walkthrough and taking a crack outright at trying to write methods and arguments that matched the tests. Often I’ll skim the walkthrough to sorta grab whatever I can in order to put the lab in context. Struggling for more than 15-20 minutes would send me to an instructor for more in depth understanding. But, also, having a ‘correct’ answer that I don’t understand and can’t refactor into some other type of code will also send me asking. Moving quickly like this made me concerned that maybe I was going too fast through some lessons, despite having the impression that the progress itself was good – something akin to skimming a textbook and getting a B on an exam. So I tried to refocus and redefine the goal… restating it plainly: it is to become an awesome software engineer. But what’s that even mean, and where is the most direct evidence of brilliant software engineering that is readily available to me?.

Thus, I felt a compelling reason to slow down – not to work differently through the labs, but to pay more attention to how the rspec tests were written. And that was my AHA moment. The realization/recognition being that the truest “expert code” was not necessarily the official solution posted on GitHub, but the rspec tests that were written to test the code. To contrast: if you look around a site like CodeWars, you’ll see plenty of clever solutions that are not self documenting – and you may even wonder what effect clever code like some of the “top solutions” posted may have on productivity at a company which employs dozens or hundreds of programmers… each with their own skillsets.

So, from there I came to the conclusion/suspicion that by studying the rspec tests, I could get a sense of how an expert software engineer thinks… moreso than from clever coding solutions.

The tests give you a sense of how an expert builds a program in the abstract (and debugs it!). In other words: if you build a house out of steel, stone, wood, or plastics they’ll all be structurally different… and yet, they will all provide the same basic function. To follow with the materials analogy, the most important aspect of the house/structure is often not “how” it is built – but how it stands up to conditions in the real world.

…………………………………………………………..

Anyways, I could be wrong. Am probably wrong. But that’s my hypothesis for now, and the thing I’m hoping to disprove as quickly as possible so I can iterate up and on to something better. Until then…